a different kind of gig

a different kind of gig

by Bobby Sweet

I am a singer/songwriter, and my life has been spent, thus far, searching under every rock for the songs that move people. In the United States sometimes it’s easy to lose my focus in the wake of our commercial mentality. The most recent “rocks” I’d been turning over on my quest were some 6,000 miles around the globe in the wilds of Argentina. I went for a whole list of reasons, at the top would be friends, inspiration, music, adventure, and culture. I had been invited there to participate in the development of a really cool artist/thinker sabbatical program. There’s nothing like the Andes to hurl your soul way out into the stars. After a total of 24 hours of travel by plane, bus, four-wheel drive truck, and horseback, I arrived in the wild foothills of Patagonia at a small cluster of Casitas (tiny houses) nestled under a grove of tall slender alamos (a species of poplar tree). This tiny community was home to me for most of my nine weeks in Argentina.

This estancia (ranch) has no power, no phones, and no roads. This is the only place I’ve ever been where you will not see, or hear an airplane, ever – it is silent. All transportation is by foot or horseback. Through the valley runs a river so pristine it is like looking through glass. The land here remains largely untouched, save for an occasional gaucho or grazing animals. The water is spring fed out of the mountains, and hot water is made via a wood fired water heater. There is a beautiful garden, surrounded on all sides by a stone wall and eight foot high hollyhocks, where all the vegetables are grown. All meat is raised on the ranch. In addition to family and friends, there are three gaucho families also living on the estancia. (A gaucho is the cowboy of this region, rugged loner types, born on horseback, expert with animals, and a genius with the simplest of tools.) Most of the chores having to do with animals are handled by the gauchos, and the rest of the day-to-day chores are divided up amongst the tiny community, ranging from five to sometimes twenty people.

The staple of the diet there is meat, usually chivo (goat). Their version of a barbecue is called asado. The gaucho starts a fire and places the salted meat on a steel spit, which is then stuck into the ground next to the fire. Depending on how many people are eating, he sometimes cooks an entire half of the animal. The gaucho tends the asado with pride, usually wearing his best. The asado is a wonderful together time for all, with wine and song, and usually friends and neighbors are invited too. It was at an asado where I first met the gaucho Oscar Beccaria.

Oscar lived next door. I n Argentine terms that meant about a one hour horseback ride down across the river and halfway up the high pass east of the estancia. Oscar was a tall man with features chiseled by the Patagonia wind and sun, which made him look much older than his 52 years. He had a jack-o-lantern smile, like a lot of folks in these parts who had no access to, or could never possibly afford a dentist. He was dressed in typical gaucho attire, black calf-high riding boots, bombachas (loose fitting pants, tight at the waist and ankle), and a faja (a colorful sash worn around the waist). Tucked in the faja behind his back, the gaucho carries his cuchillo (knife). The cuchillo is usually eight to twelve inches long and is one of the most necessary tools in his life. The rest of his attire consisted of a button-down longsleeve shirt, a handkerchief tied around his neck, and, of course, no gaucho is ever without his hat (sometimes a beret, sometimes a straight brim).

I had been singing songs that Sunday afternoon during the asado, and could tell Oscar’s wife, Violeta, was a music lover. Later in the afternoon the three of us were in the kitchen of the casa grande having a rather slow moving conversation. Conversations in Castellano, (their dialect of Spanish) always seemed to move slowly around me, not for lack of things to talk about, but due to the number of times I had to say “Como?”(what?), or “repita por favor“(please repeat that). One way or another, somehow, eventually we would understand each other. Violeta and I were chatting about music, and I expressed that I was thinking about riding to the nearby town of El Cholar to play at the school – again, nearby defined as four hours by horse. She became very excited about this, turned to Oscar, and in a flurry of Castellano told him of her idea. It turned out the two of them were going to El Cholar the very next day, and they invited me first to their puesto (a small hut made of sticks and branches) for lunch, and then to accompany them to El Cholar. It was one of those moments destined to happen, as were all the other moments in this adventure. I gladly accepted.

The next day I saddled up my horse, Cutrui, threw my backpacker guitar over my shoulder, and headed down across the big river. Crossing the river was always an amazing experience – water rushing by, the sound of hooves slipping off rocks below the current, and the occasional stumble sideways threatening to plunge you from the saddle into the cool waters. Sometimes, the water was over my stirrups as we made our way across, but somehow Cutrui always delivered me safe, sound, and dry to the other side. We made our way up the mountain to the east toward the high pass. I looked back at the ranch, and from there it was just a tiny speck far below in this amazing panorama of huge sky and mountains. I came, finally, to Oscar’s puesto; it was nestled in the shade of a grove of alamo and willow trees from which hung the hides from several sheep and what was left of a chivo carcass. The welcoming committee at Oscar’s place consisted of a dozen or so chickens scratching around the puesto in the dirt, twice as many turkeys, three working dogs, a couple of cats, and Oscar’s old mule. They were all eagerly awaiting my arrival. Oscar invited me warmly inside the puesto and offered me a seat on a rock near the fire. The rock had a sheepskin for a cushion. The fire was not a woodstove, just a ring of stones on the dirt floor in the center of this ten foot square simple hut. They had prepared an asado for lunch. (I think in my nine weeks in Argentina I consumed four goats myself.) So, there I sat with Oscar, Violeta, and one other gaucho who helped with the ranching chores. In my right hand I held a cuchillo and a big hunk of goat meat, in my left hand, a torta frita, (dough deep fried in goat grease). The wind was whipping outside the puesto, the smoke filled my eyes as I sat, nobody speaking, eating that humble meal and marveling at how alive I felt in that moment.

After eating, Violeta served a mate. Mate is the beverage of choice in Argentina, it is a loose-leaf tea, drunk from a hollowed out gourd through a silver straw with a filter on the end called a bombilla. Argentines take their mate seriously. There is a proper etiquette to serving and receiving this strong, slightly bitter herbal stimulant. Violeta served a mate like it was a holy ceremony. Since I was the guest, she served me first. There is only one server, and one mate is shared no matter how many people. Careful attention is paid to water temperature. It is the server’s job to test, and sometimes spit out, what is not deemed perfect. The gourd is handed from the server, bombilla first, and returned in the same manner. One only says “gracias” when they have had enough, not before. If you forget to say “gracias,” you will be served until your eyeballs pop out. It is proper to drink all the contents, and then return the mate to the server so they may promptly serve the next. I have grown to love all things about this Argentine custom, the ritual, the sharing, the taste, and the memories of the many I have partaken with.

When Oscar was satisfied, he stood up and walked out of the puesto. I handed the mate back to Violeta, said “gracias,” then followed Oscar. I helped him pick up and hold the huge packbags, while he tied them onto the mule. Being the gringo that I am, my mouth was hanging open at the bulk of the load that we strapped on the back of that animal. Among other things, there were blankets, cooking supplies, the meat from two goats, and a crate containing nine live baby turkeys. The mother turkey was all tied up in a burlap sack with just her head poking out, then she was tied on the back of the mule; she seemed comfortable in her first class seat. When Oscar was happy with the load, he called to Violeta and the three of us mounted up for the four hour ride.

The first hour we spent ascending up, up, up over the high pass. Oscar rode first in the line leading the mule, then Violeta, then myself. I looked on with amazement over Cutrui’s head at Oscar, his mule, and Violeta. Then I looked down at the hands, cracked and tanned from the hot sun, holding Cutrui’s reins, almost as if they weren’t my own. It was like a wild dream. The thought crossed my mind that this was the strangest and coolest trip to a gig I’ve ever had. The breeze lifted our dust cloud and scattered it across the high desert. The only sounds were wind, hooves on the trail, and the huffing and puffing of those four devoted animals carrying us up that mountain. Finally, much to the delight of our four legged companions, we reached the top of the pass. By my guestimate the elevation was around 8,000 feet. Suddenly, I was looking across lifetimes of beautiful pristine Andes mountains. The Patagonia wind was singing in my ears and making my eyes water – giving me life and taking my breath away all at the same time. It happens over and over again there, it is country that can steal a tear from your eye before you even know it. Oscar and Violeta didn’t seem to see it, they just looked at the trail probably thinking about the chores in El Cholar. I was like a six-year old at Christmastime, so alive! Far off in the distance, those snow covered giants towered over us at the border with Chile, and Cutrui and I were riding through a panoramic postcard of a Patagonia sunset.

The Castellano that the gaucho speaks is to Spanish what West Virginia hillbilly is to English. That meant I could speak clearly to Oscar, but was completely lost trying to figure out what he was saying. He did not let that deter him from wanting to know everything about life in the United States. When I became overwhelmed with how much I could not understand, I simply talked to him in English, which in turn he did not understand, and we both laughed. He asked questions like, “how much does a job pay in the U.S?” and “Do you have a television…or a car?” I became aware that, to Oscar, I was a rich man. I looked at his beautiful simple life and happy demeanor and decided he was the rich man. So, there we were, the gringo and the gaucho riding through the Andes. All of our lives we had been strangers, until now. We were from different cultures, spoke different languages, and lived in different hemispheres. Just goes to show you, that you never know where you might find yourself.

When we rode down into El Cholar just after sunset, it was like a scene from an old western movie with its dirt streets and horse traffic. There are about 800 people living there, mostly children. El Cholar has one little store that sells everything frommate to horseshoes. I noticed about a half-dozen cars that actually ran, the rest I saw were yard ornaments or served as playhouses for the kids. As I rode into town beside Oscar, I was trying to figure out how, without even speaking, I drew so much curiosity. Finally it dawned on me as one little boy was pointing – my cowboy boots had gringo written all over them. The boots are different enough that they know, “you ain’t from around here.” Of course there were probably plenty of other differences too, but they all wanted to know about the boots. El Cholar is a town that we here in America would call “depressed,” but in a town like this you can walk down the street and make twenty-five new friends by the end of the block. They say (whoever they are), that for everything you win you lose something, and I say (whoever I am) that for everything you don’t have, you’ve got something else. My next few days would be spent learning what that “something else” was in the hearts of the people of El Cholar.

At siesta time the streets of El Cholar were quiet. Everyone would go home to rest away the hottest part of the day. The days there passed like a lullaby from some sweet angel’s lips. Nobody seemed to be in a hurry, and I noticed that, under Argentina’s charm, I walked much slower myself. Lying in my room at Oscar’s humble house, I stared up at the bare light bulb hanging by the wires, and was marveling at how this family had opened their hearts and house to me. Like most of the rooms in these tiny houses, mine had a dirt floor. The house was made of adobe, heated by a wood cookstove, and was smaller than a two car garage in the States. Oscar’s entire family came to dinner one evening. There were eight people crowded around the table in Oscar’s little kitchen, all fascinated with “el gringo que canta” (the gringo who sings). Oscar referred to me as such affectionately, and I simply called him “gaucho.” I was happy to be there in the company of that family, in spite of understanding so little of what they were saying. There were a million questions, and we all laughed at all the things I just could not understand, no matter how hard they tried to explain. We lived and laughed away that evening over another delicious meal of (you guessed it!) goat.

The next day Violeta went to talk to the director at the school about the possibility of my playing for the kids. The idea was met with much enthusiasm, and it was decided that I should meet la profesora (the teacher), Mariana, who incidentally had begun teaching a little English in the school this year. Later in the day, I was escorted by Oscar’s daughter, Mabel, and her friend Patricia to Mariana’s house. Mariana was very excited about this idea, and asked if I could come to the school to play at 8:30 that night. El Cholar has so many kids that there are three shifts to the school day. The youngest kids go from 8:00-12:00, middle aged kids from 1:00-5:00, and the older kids from 5:30-9:30, all to the same small building.

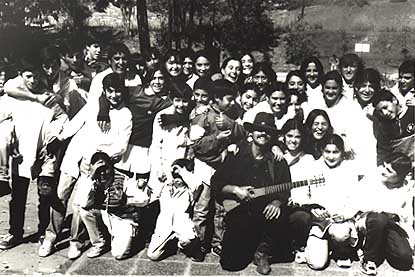

I rode Cutrui down to the school at about 8:15. The buzz had already gone around about “el gringo que canta,” and I was met enthusiastically by a group of kids before I even got to the door. Like my own little Castellano body guards, they escorted me into the building. Mariana met me in the hall with a warm smile. We discussed how I would speak to the kids very slowly in English first, then in Castellano (if I knew how to say the same thing). You could feel the energy buzzing outside the door, and they all just started applauding as I walked into the classroom. It took a couple of minutes for them to settle down, since they had to point out, and discuss with each other, my boots and odd shaped backpacker guitar. After they were quiet, Mariana introduced me, which summoned another round of excited kid applause. Then, I said “hola,” they said “hola” back, and I started to talk about where I was from and about the musical life in the U.S.

I couldn’t put my finger on it, but there was just something different about this group of high school aged kids. It could have been partly that I was just such an exotic bird to them, but I felt something more. I can only describe it as a warmth: deep, subtle, and welcoming – the way the sun feels on your skin after a long cold winter. They sat completely silent as “Believer,” a song I had written a week prior on a remote solo camping trip, filled the room. By their gratitude you’d have thought I handed them each a thousand pesos. They recognized some older tunes from the States by artists like John Denver, Creedence and Kenny Rogers, but, since this town is largely unplugged from the rest of the world, they didn’t seem to recognize anything too current. I played for about a half an hour, with my bi-lingual mutter in between songs. After the music we talked about differences between our two cultures, and they asked painfully sweet questions about TVs and cars. The funniest question was “conoces los Bastie Boys?” (They had a hard time pronouncing “beastie.”) Translation: Do you know the Beastie Boys? We had an absolute blast. Mariana was so excited she asked if I could come back to sing for the younger kids in the morning; gladly I agreed. Again, the morning group of kids was so cool, all clapping hands and all of us laughing at my broken spanglish. They wrote pages of sweet thank yous in my travel journal. As I was leaving the school, Mariana stopped me in the hall and asked if there were any way I could stay one more night and play for the people of El Cholar. She explained how “these people have nothing here.” If they have a television (there are a few), there’s one channel, and they have “Radio El Cholar” which broadcasts for 3 hours in the morning and 3 hours after siesta – that is all. I rode back, talked it over with Oscar, and decided to stay another night. As long as I live I’ll be grateful that I did. As soon as Mariana heard that news, she sent a kid on the run to “Radio El Cholar,” and word went out: “un musico de Los Estados Unidos” would be playing at the hosteria that night. The hosteria is the only place in town you can rent a room, and its little dining room/lobby was to be our concert hall.

I rode into town on Cutrui at about 9:15 for the 9:30 start time. I laughed out loud as I slung down from the saddle with my guitar, at the movie that was unfolding around me. I tied Cutrui to the fence out front, and walked inside. Somewhere in town they had found a “microphono” and a little guitar amp that sounded like it had a blown speaker – soundcheck was short. By 9:30 a large percentage of the population of El Cholar was jammed into this little room, and I doubt we could have fit one more. Oscar made it his job to count heads, and he figured more than two hundred fifty people were there. The kids got a real good look at my boots as they sat as close as they possibly could all around me on the floor. I was feeling the same warm feeling that I had in the classroom, but now at four times the magnitude. Those who couldn’t fit in were milling around outside the open doors and windows. This, incidentally, was also my first time away from the estancia where there was no help with the language, but I would soon learn first hand that a song needs no interpreter.

I stepped up to the mike like so many times before, but this time was completely different. “Hola,” I said, and the roof almost lifted off the hosteria. If ever I felt like I was playing to people who truly needed a song, it was this night. They re-defined the expression “you could have heard a pin drop.” I looked to my right at one point during the concert and all the windows were full of faces peering in, and behind those faces, standing in the now darkened street, was my horse, tourbus on four legs and faithful friend – Cutrui.

I played songs I had written during my time in Argentina, and told the crowd in Castellano how they had come to be and what they were about. If I got stuck with the language, somebody in the front row was happy to help me conjugate a verb. I was even so bold as to sing a translated version of one of my songs in Castellano. The concert was about two hours long and felt like two minutes. I could have played all night surrounded by these loving, polite, enthusiastic, and grateful Argentine people – a big family with big hearts. We laughed, we cried, we lived, and, as we all left the hosteria that night, the world seemed like a better place. After more than twenty years of playing for people, I had the absolute blessing of the opportunity to share music in an environment completely new to me. In doing so I experienced the raw exchange of love and energy in the big hearts of the people of El Cholar – people who open their hearts and houses and give you everything when they have nothing – all for a song. This was not about selling a CD, or getting a good review. There was not one poster or newspaper add, just an announcement on “Radio El Cholar” five hours before the gig. I thought about all the antics we musicians will go through in the States in hopes of singing to a room full of people and had to laugh.

After everyone left, I walked into the now empty darkened street, slung my Martin backpacker guitar over my shoulder, thanked Cutrui for hangin’ out, and mounted up for the ride under the Patagonia stars back to Oscar’s house. I lay awake most of the quiet Argentina night drifting in this dream of El Cholar, music, and life.